Lithium is the commodity on everyone's lips right now, but is it really the next big thing in mining in Australia?

Until recently, lithium was one of those commodities very few people would have given much thought to. Increasingly, however, lithium is the word on everyone’s lips. It was certainly a “water cooler” topic at the recent Diggers and Dealers conference in Kalgoorlie.

Why? Because electric cars need lithium for their batteries — and electric cars are, we’re told, the future. Lithium, together with cobalt and a few other minerals essential to battery operation, are suddenly all vital commodities.

So, is lithium really the “next big thing”? The figures certainly seem to confirm it.

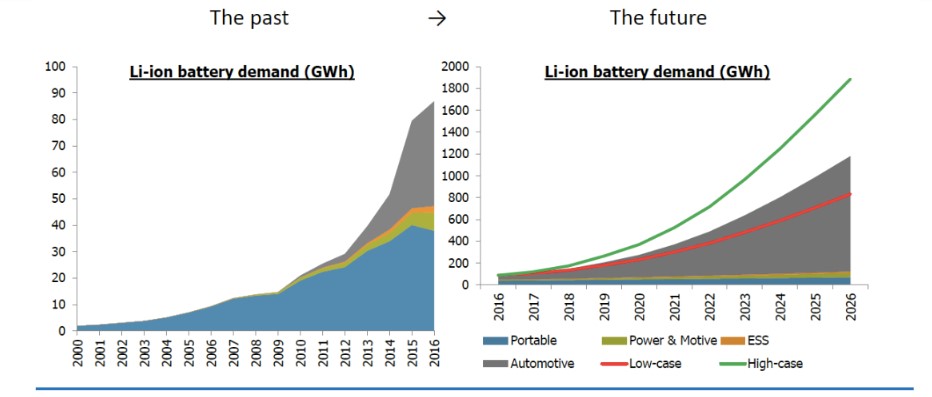

During his Diggers presentation, Pilbara Minerals Chief Executive Ken Brinsden showed a table indicating the historic and future demand of lithium, worldwide.

Source: Roskill.

“More than US$20 billion of committed investment (in the lithium industry is) expected to result in new battery manufacturing expansions that will increase global production capacity significantly and drive production costs down,” Brinsden said.

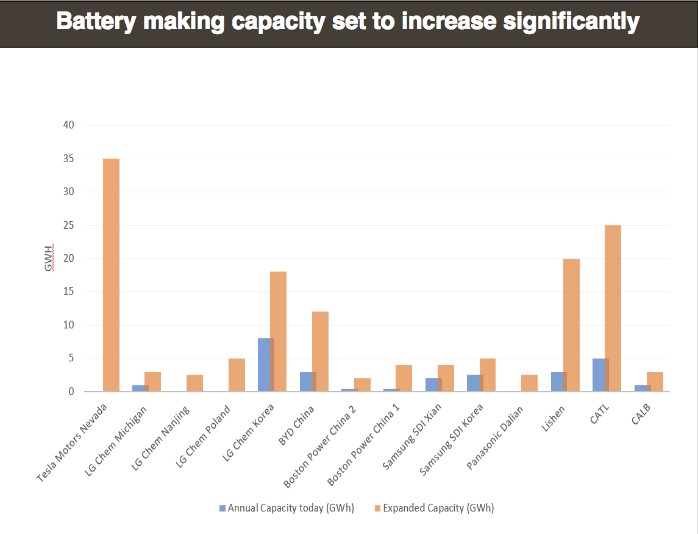

Here’s another chart showing just how battery manufacturers, including Tesla, are ramping up their capacity over the short-term.

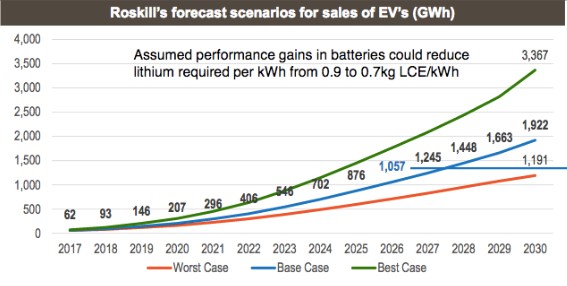

And here are the forecast sales of electric vehicles, to 2030.

With potential like that, it’s not hard to see why miners, explorers and investors are taking a close look at lithium.

Senior Client Advisor at Bell Potter Securities in Perth, Michael Grant, said what’s driving lithium’s value is, in particular, the Chinese electric vehicle market.

Lithium is another China growth story

“This is another China growth story,” he said. “In May production of ‘new energy’ vehicles in China grew by 38 per cent on an annualised basis. That growth is phenomenal and it’s continuing. It’s a global market that’s being driven by Chinese demand.”

While people the world over seem excited about Elon Musk and his Tesla cars and batteries, Grant believed electric cars in particular — and therefore demand for lithium — was going to benefit from China’s burgeoning middle class.

“China doesn’t have the legacy issues like other markets,” he said. “In places like the US people already have cars, so they have to decide what to do with their old vehicle, for example. That’s not the case in China.”

What does lithium mean for mining jobs?

So, what does that mean for Australia and for mining jobs in Australia’s soon-to-be-growing lithium industry? Let’s look at Pilbara Minerals’ example as a starting point.

Pilbara Minerals is ramping up development of its $234 million lithium-tantalum project, Pilgangoora, in the West Australian North-West. It has Chinese offtake partners committed to taking 100 per cent of the lithium it produces in the first stage of development. That’s 170,000 tonnes per annum.

According to statistics reported in Bloomberg recently, Australia is the world leader in lithium production, with an output of 14,300 tons in 2016, accounting for 40.5 per cent of the world’s total.

“It is also home to the largest and oldest lithium mine, the Greenbushes mine, owned by Tianqi Lithium and Albemarle,” the report said. “Chile, the country with the second-largest production, has the world's largest reserves of 7.5 million tonnes, accounting for 51.8 per cent of the total. Lithium extraction methods differ in Australia and Chile, as Australian lithium reserves are mostly hard-ore, while Chile reserves are in brine deposits. Technology in brine extraction has improved and may be more cost-competitive than ore crushing in future.”

So if lithium really is the future, many of the mining jobs will be in Australia.

Australian mining industry taking lithium’s potential seriously

And the local industry, as you’d expect, is poised to capitalise on the potential.

“With any one of these emerging demands for a particular mineral, particularly in Australia, what I see every time — it’s almost a cycle — you get these very early speculators who change their name to say they’re an explorer of lithium,” he said. “There’s always someone who jumps in and puts a label on their company and hopes to get some credibility.

“Out of that usually emerges a few serious producers who have actually gone and bought an existing prospect or asset that can produce relatively quickly — and you have that now; you have a few companies, like Galaxy, that are pretty much headed towards production.”

But it won’t all be smooth sailing, as Pilbara Minerals discovered in 2016. The hype around lithium saw their share price soar to 87c, compared to today, where it hovers around 38c. As Brinsden told the Diggers’ crowd: “A lot of people got burnt. But they’re coming back now.”

There have also been issues with production timelines for many miners, as Grant explains: “The quality of lithium concentrate required for either EV or standard stationary batteries is very high, so the processing has to be spot-on and the starting product has to be spot-on, with no impurities.”

“The mining process is the lead-in to that and we’ve seen some delays. If I’ve had some doubts or I’m watching for something to go wrong, it’s potentially because of those delays.

“The Australian companies are primarily mining from hard rock-based sites, so their costs are reasonably high compared to existing global markets, so there is the potential for complications either leading up to start-up or post start-up. There are a couple of examples where companies have started mining and they’re still running at 50 per cent of their utilisation because of some technical issues. Like any relatively new industry, there are going to be trips along the way.”

Core samples from Rio Tinto’s Jadar lithium deposit in Serbia.

Bigger mining companies likely to succeed with lithium

But the bigger end of town is likely to succeed, Grant said. He points to Rio Tinto as an example. Rio holds something of a “golden egg” — the 200 million tonne Jadar lithium and boron deposit in Serbia that, once developed, contains enough lithium to supply 10 per cent of global demand. The company has recently upgraded the status of the deposit to one of its most likely growth projects, revealing that if it gets approval and the economics support it, it will start construction of the mine in 2020 and start producing from 2023.

What effect would such a massive mine coming onstream have on the Australian lithium industry? Analysts aren’t sure. Hartleys Head of Research Trent Barnett told The Australian: “There is uncertainty as to how big lithium market demand will be, with forecasts ranging from 500,000 tonnes a year to well over 1 million.”

He warned that if Rio developed Jadar chiefly for its boron, and lithium became a by-product not dependent on prices, that could weigh on the lithium market if demand was not strong.

Demand is the great unknown here. Could lithium be today’s version of graphite, which got everyone excited a few years ago but then fizzled out? (Or indeed, could lithium be today’s lithium, as the commodity has caused excitement that came to naught in the past). Only time will tell.

For his part, Grant says the potential demand not just for electric vehicles but for stationery home battery packages and other new technologies, including solar applications, all feed into the demand for lithium.

“We just don’t know how big that could be,” he said.

Mining People International has an experienced team of mining industry specialist recruiters ready to help you find your next opportunity in mining. Contact us today.